Construction

First Sacramento Site

In 1856, Sacramentans selected a city block, bounded by I, J, 9th, and 10th Streets, as the future location of the Capitol building. Construction was halted after only 11 days due to legal challenges. Control of the site reverted back to the city, and the location became a public plaza instead.

Fearing that Sacramento’s position as the capital of California was in jeopardy, the Legislature pushed forward legislation that finally secured the city’s designation as the permanent seat of the state government. Four blocks were purchased to serve as the new site for the Capitol building: between L, M, 10th, and 12th Streets.

Several competing designs were submitted for the Capitol structure. Those drafted by Miner F. Butler, the first of seven architects who would work on the project, were accepted. Reuben Clark – who drew Butler’s original plans – quickly took over from him as the next architect.

It would take 14 tumultuous years to complete the construction of the Capitol.

14 Years of Construction

Groundbreaking for the Capitol building took place on December 4th, 1840. It took over a decade and several administrations to complete the construction effort due to funding issues, flooding, labor and supply problems, and political strife. Late in 1869, the Capitol was partially completed and able to accommodate the Legislature and several state officers, including the Governor. It would still take an additional five years to finish the building.

Completion of the Capitol project came at a high cost for one of its principal architects. In 1865, Reuben Clark was admitted to a Stockton mental institution where he died a year later. According to the hospital’s files, the cause of Clark’s mental instability was diagnosed as “continued and close attention to the building of the State Capitol in Sacramento.”

Gordon P. Cummings, the third architect to take charge of the Capitol project, took over for four years after Reuben Clark’s departure. The fourth and fifth architects, Kenry Kenitzer and A. A. Bennet, continued work on the structure between 1870 and 1872. Bennet also began construction on the Capitol grounds and a mansion for the Governor.

Cummings returned to his role as supervising architect in 1872 and completed the project two years later. On March 31st, 1874, the State Board of Capitol Commissioners suspended all further work on the Capitol building.

Funds

The lack of adequate funding for the Capitol construction project frequently hindered progress. The Legislature, which met for only two months every year, was responsible for providing funds. Building progressed until finances were depleted, unable to resume until the next legislative session.

Another financial delay in the completion of the Capitol was the refusal of workers to be paid in devalued paper currency. California was a “hard money” state – meaning that physical coins or precious metals were the only acceptable currency. The political turmoil of the Civil War had significantly decreased the value of paper money, or “greenbacks”, which were refused for transactional use and valued at only pennies on the dollar.

In his annual address to the Legislature on January 9th, 1860, Governor John B. Weller addressed the persistent funding issues, declaring: “It is believed that $500,000 will put up a wing sufficiently commodious to accommodate the Legislature and state officers.” 14 years later, in response to numerous obstacles and inflation, the Capitol’s price tag had grown to $2.45 million.

Floods

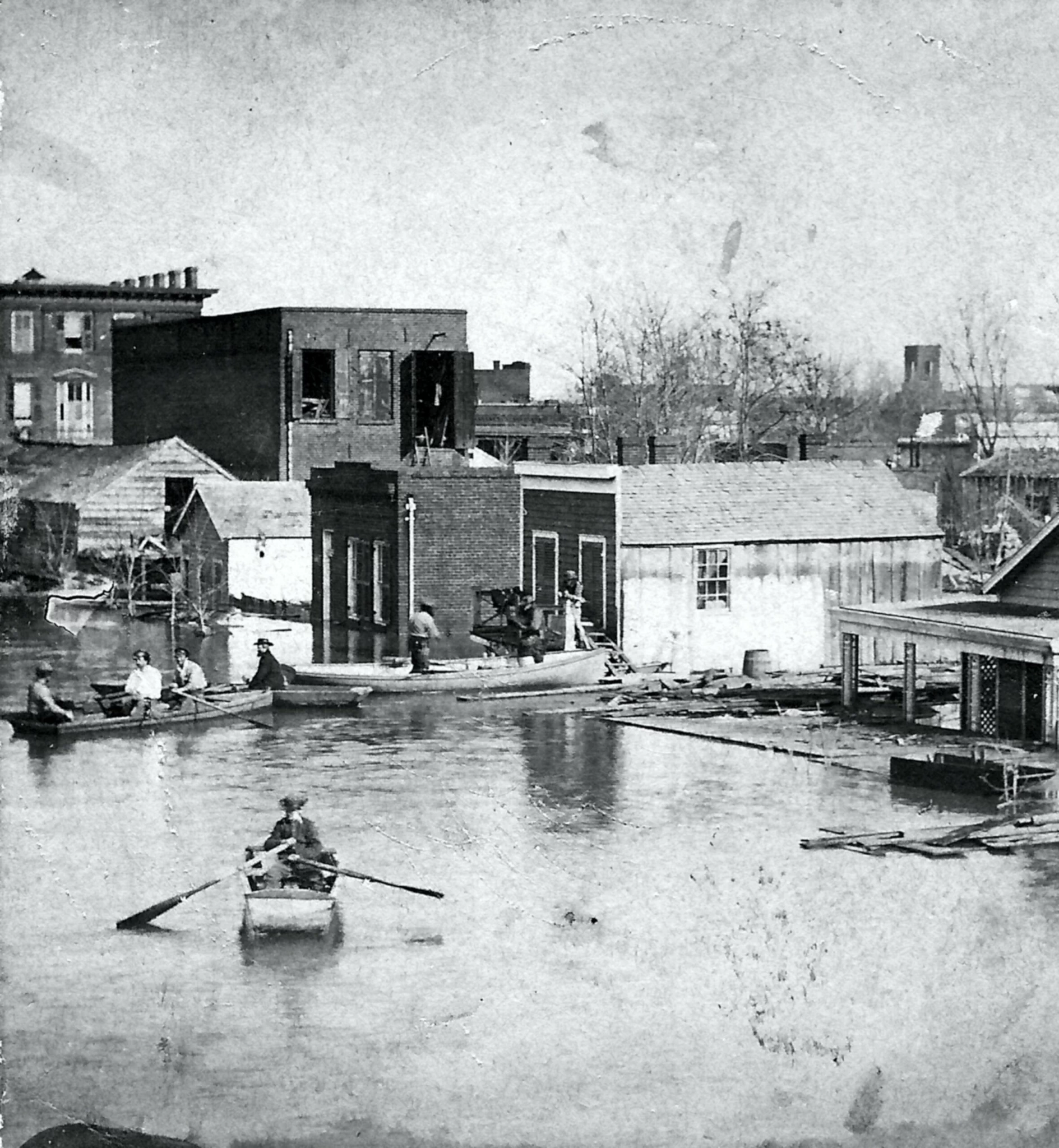

Heavy rains, beginning in December 1861 and continuing into January, caused a series of levee breaks along the American River that flooded Sacramento and the Capitol construction site. On January 6th, 1862, the Legislature convened in the midst of the deluge. The fourth in a series of floods inundated the city on January 11th, and the Senate passed a resolution to adjourn to San Francisco for the remainder of the session.

The Assembly, however, did not concur and passed a resolution authorizing the Sergeant-at-Arms to hire boats to convey legislators to and from the Sacramento County Courthouse at 7th and I Streets. Discussions regarding a permanent relocation of the state capital were rekindled.

Ultimately, the rising water was too much for the legislators to bear. They briefly adjourned before completing the session in San Francisco’s Merchants Exchange Building from January 24th until May 15th, 1862.

Work on the Capitol began again in August 1862. Construction crews hauled away wheelbarrows of dirt to raise the building’s elevation by six additional feet and avoid future flood damage. In the process, the original first floor of the Capitol was turned into the basement.

Construction Troubles

The Board of State Capitol Commissioners, the group placed in charge of the construction project, faced many additional problems.

The original builder, Michael Fennell, was relieved shortly after construction began in 1860 when work did not progress on schedule. In August 1861, G. W. Blake and P. Edward Conner received the contract instead.

Blake and Conner immediately faced difficulties obtaining the cement, lime, and granite needed to continue their work. The floods of 1861 and 1862 brought construction to a halt. The Capitol building’s walls were surrounded by a foot of water and many construction materials were destroyed. The builders requested an extension to their contract, but the Board of State Capitol Commissioners denied it.

From that point onward, work on the Capitol project was completed using a “day’s labor” system. Supervising architect Reuben Clark sought to avoid delays by acquiring materials by contract and hiring all laborers by the day. While this haphazard method did not fully end the delays and controversies, it remained in effect until the Capitol’s completion in 1874.

Political Opposition

Even after the Capitol construction project was underway, some legislators argued that the permanent seat of the state government should be moved elsewhere. Political opposition continued for many years. There were unsuccessful efforts to relocate the capital to Oakland (1858-1859), San Jose (1875-1878, 1893, and 1903), Berkeley (1907), and Monterey (1933-1941).

A Contrast in Granite

A close look at the western façade of the Capitol reveals two different types of granite: a dark gray granite from the Folsom area called “Ambassador Black,” and a lighter-colored Rocklin stone, “Sierra White.”

The original plans for the exterior of the Capitol building called for the use of cast iron and stucco. In 1863, the supervising architect, Reuben Clark, suggested that stone would be more suitable for a public building of such importance.

Acting on Clark’s recommendation to use stone, the Board of State Capitol Commissioners drafted a contract with a sandstone quarry in Yolo County. Upon inspection of the sandstone, however, the state geologist found that it was too dark and would not weather well. He considered granite a better choice for the project. He also argued that granite could be brought from the Sierra Nevada by rail far more cheaply than the sandstone could be transported from Yolo County.

A Railroad Rivalry

The two variations of granite used to construct the Capitol’s façade are representative of a rivalry between two railroads – the Sacramento Valley Railroad and the Central Pacific Railroad. The two companies were in fierce competition to become the first railroad to cross the Sierras, benefit from the Nevada silver rush, and link up with the planned transcontinental railroad coming from the East.

The granite for the first story of the Capitol was quarried in Folsom and transported to the building site on the Sacramento Valley Railroad, the first railroad in the American West. Reuben Clark found this granite unsatisfactory in February 1864. He reported that it was difficult to cut, as it was “of bad rift, with black knots, and by reason has caused us much expense.”

The Legislature considered a bill to aid in the construction of the Central Pacific Railroad. At the time, the Governor of California, Leland Stanford, was president of the company. In return for receiving military and other transportation services, the Central Pacific Railroad agreed to allow the free transport of construction materials to Sacramento. A granite quarry on the railroad line, near Rocklin, was also given to the state. This new contract provided the transcontinental railroad with its first profits.

Contract Granted to Rocklin

The state geologist gave the Rocklin granite a favorable recommendation and encouraged the Board of State Capitol Commissioners to open bids for quarrying the stone. On August 16, 1864, a bid of 58 cents per foot was accepted. Since the Folsom granite was prohibitively expensive, work on the façade stopped in November 1864. Only half of the Capitol’s first story had been constructed. Three months later, the first load of Rocklin granite arrived, and construction began again.

Plans to complete the remaining three stories in stone were scrapped due to overspending. Instead, brick made from local limestone and clay deposits was used as a cheaper alternative. Up to 20,000 bricks per day were required to complete the unfinished portions of the exterior. It was further decided to construct the dome framing from iron rather than wood – a major architectural innovation.

Cast Iron Columns

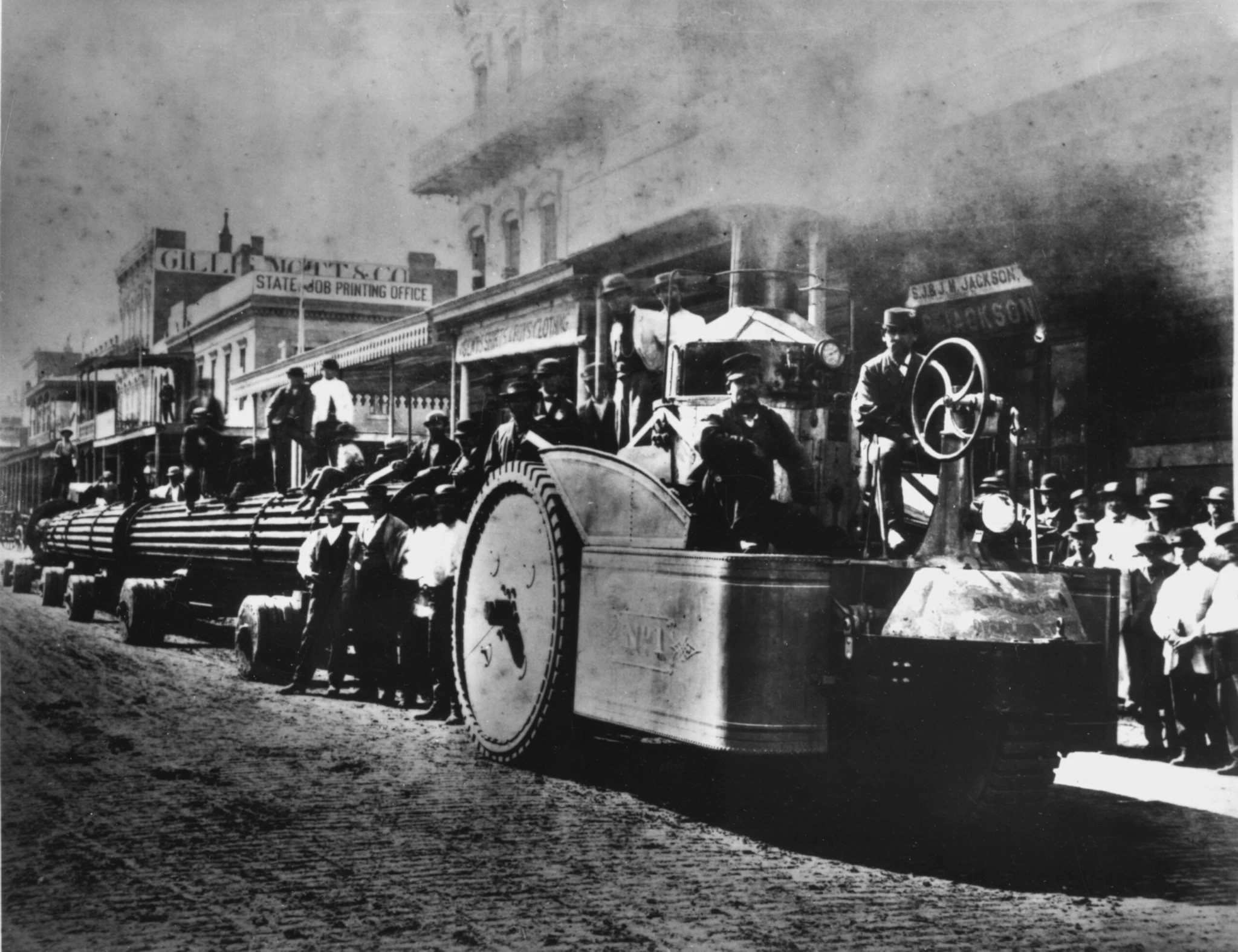

Cast iron was used to reinforce the Capitol building’s beams, arches, columns, and other details. The 16 Corinthian-style columns, used to create the colonnades for the Capitol’s three porticos, were manufactured in San Francisco in early 1871. Each column measured 30 feet long, four feet in diameter, and weighed eleven and a half tons.

After being shipped by either rail or boat, the columns were offloaded at the Sacramento waterfront. They were then hauled approximately ten blocks to the building site by a steam-powered tractor. This tractor was a cutting-edge invention, though it moved only one mile per hour over the 0.75-mile route to the Capitol.